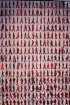

In a disembodied machine voice, the Borg, the cybernetic collective, ask the predominantly human crew of the Enterprise to surrender. The Borg collective assimilates all life forms of interest to them, incorporating their biological and technological characteristics and knowledge, but also their thinking, acting and feeling.

New technologies permeate our everyday life and inscribe themselves into almost all areas of life. We live in a world that is controlled, managed and increasingly constructed by devices and applications. The digitalization of communication and control systems enables a well-camouflaged way of exerting influence, in which users are manipulated according to the goals and interests of economic and/or political associations. Not only are enormous flows of money on the stock exchanges and the associated global effects controlled by algorithms, and the new possibilities in social media allow manipulative influence - e.g. on elections - to be exerted: our bodies, our thinking and actions are constituted by new technologies. Control and censorship are integrated into our activities through our own actions, using mostly uncritically hardware and software. Surrounded by app-controlled devices such as smartphones, smart watches, fitness bracelets, televisions, refrigerators, security systems, smart Barbie dolls, etc. that communicate via the Internet, we live in smart homes in smart cities. No face, voice, emotion, movement or (buying) behavior escapes these devices and applications. They collect data, feed the systems that evaluate us and decide on the allocation of insurance premiums, loans, housing, jobs on the job market, etc. We have willingly handed over control to systems.

On the one hand, there are technologies that construct cyborgs by changing the structure of the body, on the other hand, there are technologies that are used in our environment that have a significant impact on our thinking, behavior and actions. Already in 1985 Donna Haraway described in her "Manifesto for Cyborgs" the transition from an organic industrial society to a polymorphic information system in which knowledge, technological processes, but also people and other organisms are broken down into units of information. Everything becomes codable, everything becomes calculable and thus usable and controllable. But where, as Frieder Nake puts it, is the right to be unpredictable as a human being?

For the first time in history, we are enabling AI-driven technologies to act "independently". Technical devices thus become "subjects" that ruthlessly invade our privacy. "Whether technology accompanies our lives or shapes them is not the same", Richard David Precht formulates in "Artificial Intelligence and the Meaning of Life" (2020). Moral decisions, unlike scientific knowledge, cannot be objectified without reservation. Moral dilemmas cannot be solved quasi objectively by millions of online surveys (Moral Machine) about the sum of the largest accumulation of similar judgements. Quantity is never identical with moral quality. "Morally prudent robots with human values seem to be absolutely necessary to many politicians, managers, journalists and scientists," emphasizes Precht, "because for some, "ethical" programming is inevitable if only to enable people to determine the future motives of a strong AI before it does so itself. That everything that computers and robots do would then automatically be morally correct and fully verifiable is highly doubtful. "Morality without subjectivity is no morality and subjectivity without morality is no subjectivity. Moral judgements do not consist only of results or even 'solutions', but the path, the act of decision, is itself of utmost importance," emphasizes Precht. "Machine ethics demands that machines should not be programmed 'ethically' themselves, i.e. that decisions be made that judge people. To deal ethically with machines is the opposite of programming them 'ethically'.

How will we as cyborgs, as hybrid creatures - not only as a hybrid of machine and organism, but also as constructs in which individual and social perceptions and projections, realities and fictions merge with one another - perceive or lead our lives in these digitalized cities and how will we help shape society? What rules should a digital code, which we have to work out like a new social contract, lay down in view of the possibilities of digital technologies to generate something like "hyper-intelligence"? How would Isaac Asimov formulate his Robotic Laws (1942) today? The Robotic Laws from the short story Runaround can be found in an imaginary manual for robots in its fifty-sixth edition from 2058:

1. a robot may not injure a human being or, by inaction, allow a human being to be injured.

2. a robot must obey orders given to it by a human being - unless such an order would conflict with rule one.

3. a robot must protect its existence as long as this protection does not collide with rule one or two.

Verwendete Literatur:

Isaac Asimov, The Naked Sun. Doubleday, 1975

Nick Bostrom, Superintelligenz. Szenarien einer kommenden Revolution, 2018

Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman, 2013

Ollivier Dyens, The Emotion of Cyberspace: Art and Cyber-Ecology, 1994

Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century, 1984

Donna Haraway, Unruhig bleiben. Die Verwandtschaft der Arten im Chthuluzän, 2018

Katja Kwastek, „Wir sind nie digital gewesen. Postdigitale Kunst als Kritik binären Denkens“, in: KUNSTFORUM International Bd. 243 Now. – Dez. 2016, hrsg. Franz Thalmair

Dagmar Fink, „Ein Fisch im flaschengrünen tiefen All? Oder: wie Feminist*innen die transhumane Figur d* Cyborg kaperten und zu compost verarbeiteten“, in: FIfF-Kommunikation 3/16

Dagmar Fink, Wir Sind die Borg! Cyborgs queer gelesen, luxemburg 3/2015

Susanne Lettow, „Biokapitalismus und Inwertsetzung der Körper. Perspektiven der Kritik“, in: PROKLA 178, 45. Jg., Nr. 1, 2015

Richard David Precht, Künstliche Intelligenz und der Sinn des Lebens, 2020

Roland Schappert, „Digitalisierung heute. Wert und Legitimation“, in: KUNSTFORUM International Bd. 252 Feb. – März 2018

Herbert A. Simon, What Computers Mean to Man and Society, 1977

Franz Thalmair, „Postdigital 1. Allgegenwart und Unsichtbarkeit eines Phänomens“, in: KUNSTFORUM International Bd. 242 Sept. – Okt. 2016

BULLETIN ETH Zürich Nr. 286 August 2002